I used to think ski instructors were the most patient people around. That based on having myself tried to teach a friend or two to ski, and constantly being baffled by their inability to grasp a concept as simple as the snowplow: Pinch your knees in, weight the inside edge of your skis, turn. What could be more simple — SO WHY DON’T YOU GET IT?

Sorry. Didn’t mean to raise my voice.

I held that conviction for 35 years. Until I met Scott Wood and Jim Coveney.

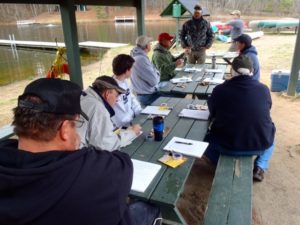

Scott and Jim teach the daylong Intro Fly Fishing clinic for Great Outdoor Provision Co. In addition to being expert fly fishermen, they are gifted in the art of cheerful tolerance and eternal optimism.

“Let’s see what we’ve got here,” Jim said as he walked over to examine my hopelessly tangled tippet, the microscopic microfiber that links the slightly thicker leader and the heavier line, with the lure.

I looked around and remarked that no one else seemed to be inventing new knots with their line.

“Nah,” he replied. “This is the third one today I’ve had to untangle.”

Patient and diplomatic.

“Fly fishing,” Scott assured us at the start of the clinic, “can be as involved as you want it to be. You can build your own rod, do your own line, make your own flies. Or you can walk into your fly shop and have your fly guy do it all for you. With the flies, there are some for very specific circumstances, some designed for specific fish, and some that will catch any fish, anytime, anywhere.”

That came as a relief to those of us who weren’t sure we were up to the lifestyle commitment that’s long been the lore of fly fishing. Whether it’s immersing yourself in cult fly fishing author John Gierach, watching “A River Runs Through It,” for the 43rd time, or camping out at your mailbox in anticipation of your quarterly issue of “The Drake,” fly fishing has long had a certain (nose-in-the) air about it.

“We are a bunch of snobs,” Scott said with a laugh.

Were is a more apt tense.

Fly fishing: Then and now

Not all that long ago buying fly fishing equipment had a “If you have to ask … .” sensibility about it. Rods alone ran for $400 to $500, then there was the reel, the flies, the creel, the net, the waders, the nifty vest … . The kids need braces? I need a 9-foot rod for that amberjack waiting for me off the coast.

But over time, the outdoorsman has been offered a growing number of outdoor options, and manufacturers and outfitters have come to a realization.

“They realized the gear didn’t need to cost nearly as much as it did,” said Jim.

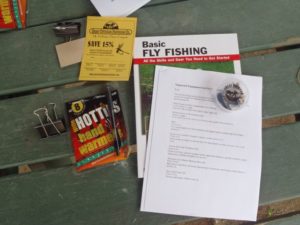

Today, you can get outfitted with good, basic gear — rod, reel, a handful of flies and fly box — for around $200. Which was part of the reason I trusted myself to take the day-long GOPC class: If I was smitten I probably could get a requisition through the house appropriations committee.

Our class began by debunking the pure-simplicity myth of fly fishing: a rod & reel, some line — how much more Huck Finnish could it get? Fly fishing is simple, it turns out, if you want to focus on a specific type of fish. If you’re interested specifically in mountain trout, for instance, you’ll need an 8-foot rod with 5 weight line. But if you want that offshore amberjack you’ll need a 9-foot pole with 12-weight line.

And that just covers two of the main types of fly fishing done in North Carolina: trout in the mountains, salt water fish at the coast. There’s also a third, easily accessible category in the Piedmont, the broad panfish/brim category found in rivers such as the Eno, as well as lakes and small farm ponds.

“You could have a bunch of rods,” Scott said, “but really, you’d probably be fine with just two.”

Though most of us in the class were north of 50, we started acting like fidgitty 10-year-olds after an hour and a half. And not just us; as Jim was trying to tell us about the various feeding columns in a body of water his head kept snapping back toward the lake every time he heard a fish brake the surface. It was time to let us grab our rods and cast.

The cast: Simply (and devilishly) deceptive

In a previous life I was a bait fisherman. Between the chunky worm, the weights and the bobber, you could rely on gravity to place the hook where you wanted it. In fly fishing, with very little weight to guide your fly, gravity takes a backseat to skill, finesse, patience.

Scott proved the perfect poster boy for casting-made-easy. With a slight twitch of his right forearm his rod rose, the line gracefully following it out of the water. At one o’clock his forearm paused for a two count as 15 yards of line gracefully unfurled behind him. Then, just as the line straightened out, his forearm came forward, his wrist snapped, the line reversed course and again, gracefully, straightened out across the water. Could it be any easier?

Maybe not after you’ve been doing it for 30 years, like Scott has.

Curiously, I think this is where I became smitten. Jim spent at least 15 minutes painstakingly correcting and critiquing my cast. On one attempt my backcast would be fine, but my forward stroke would fizzle. Then I’d be so focused on my forward stroke that I’d completely space out my backcast. About every 15 casts I’d get one that remotely resembled a true cast. Then I’d be back to square one.

“It’s the most fun and frustrating thing you’ll ever do,” Jim assured me.

We broke for lunch, then spent an hour and a half talking flies. Flies, I quickly learned, is where the separation occurs between the occasional recreational fly fisherperson (GOPC’s clinics typically are 25 percent female) and the enthusiast who blows his retirement on a fly fishing trip for salmon to Murmansk. I couldn’t envision reaching the point where I huff at a store-bought elk-wing fly because its hackle wasn’t convincing enough. Basically, what I took away from the fly session is that trout are discriminating and will only go after something that looks like it should be eaten, and only something that should be eaten in season. Bass, on the other hand, will go after anything lively and fun, even if it bears a smiley face.

We learned our basic knots and, with two hours to go, were ready, finally, to fish.

Go fish

The Great Outdoor Provision class takes place on Clearwater Lake in Chapel Hill. The lake is remarkable for two reasons. One, it sits in something of a bowl, surrounded by hills that block cell reception and give the lake a mountain feel. And two, that mountain feel is enhanced by the fact that every fall a local fishing club stocks the lake with about 1,600 trout. Not little guys, either. Because the trout can only survive Piedmont waters in cooler months, these trout come from the mountains ready to grant bragging rights.

At least that was the impression I got from the healthy trout my classmates were hauling in.

“Let’s try this,” Jim finally said after an hour of faulty casts and no bites. He took the black wooly bugger off my tippet and replaced it with two flies, a wet one about two feet from the end of the tippet and a dry one at the end. The wet one was intended to sink and draw attention, the floating dry guy was supposed to look tasty. Which it apparently did not.

“Let’s try this,” Scott said dropping by 45 minutes later. He replaced my tandem fly setup with a yellow streamer, which I remember him telling us earlier could catch anything. He sent me to the far side of the lake, where the low hills were starting to cast late afternoon shadows over the water.

I stood on the dock, backcast, caught my streamer on a wooden rail. My second cast reached out about 15 feet. Nos. 3 and 4 slightly farther. Then, I seemed to hit a groove. The casts were far from Scott-Wood-pretty, but they were getting out there 15, 20 yards. I slowly retrieved the line, the tip of my rod barely out of the water, my fingers sensitive, remembering from my bait-fishing days that tell-tale pop when a fish —

Takes your fly!

I pulled, it fought, I pulled, it went slack — then it was back. Ten yards out I could see it, a brook trout, deep green on top fading to silver. I grabbed my net, retrieved more line, slid the net just below the water’s surface and gently lifted a 10-inch brookie above the water. A nice fish made on a decent cast. More than just reward for an eight-hour day.

I admired the fish a bit longer, took a picture with my phone, gingerly extracted the hook from its mouth then gently cupped it and held it underwater. After a few seconds it twitched, twitched again and slowly slipped away.

As I watched it swim off I had what certainly was a common thought for a newly minuted fly fisherman assessing his day: There must have been something wrong with the hackles on those flies I’d used earlier.

That, I promised myself, won’t happen again.

* * *

The tackle box

Poke around, chances are you’ll find what you need to learn more about fly fishing.

- To learn more about the Great Outdoor Provision Co.’s Fly Fishing Classes, held in both the Triangle and Triad, go here.

- For stories on gear, places to fish, how to go after certain types of fish and more, visit the GOPC fly fishing archive, here.

- For a sense of the modern fly fishing scene in its various shades, check out The Drake magazine, here.

- Love a good fish tale? Colorado writer John Gierach tells especially good ones. View his work here.