The three teenage girls sat on the stone steps at the Ledge Spring trailhead, parallel texting and oblivious. All wore sunglasses, all were elsewhere. Sensing my approach, one leaned slightly, thumbs continuing to hammer her tiny keyboard. I managed to squeeze by. At least they’re outside, I thought, trying to put some positive spin on the scene yesterday afternoon at Pilot Mountain State Park.

Less than a mile down the trail I stumbled upon another young threesome. This one needed no spinning.

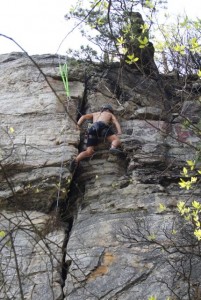

Matthew Meinzer was two-thirds of the way up a vertical crack on Your Grandpa’s Belay, a 5.7 route in the park’s Little Amphitheater area. Quinlin Riggs was on belay, offering insight. Carson Fawzie was on deck, providing color commentary. Respectively, they are in the 12th, 11th and 9th grades at Cary’s Panther Creek High School. They were taking advantage of the convergence of a gorgeous spring day and spring break in the Wake County schools to engage in one of their many, it turned out, outdoor passions. And they were more than happy to entertain an older fellow with a camera and lots of questions.

“Let’s see, we’ve done Papa Bear, Mama Bear, That-Crazy-Thing-That-Leonard-Did, Place Your Bet,” Quinlin rattled off when I asked what they’d climbed so far.

That-Crazy-Thing-That-Leonard-Did? Is that the name of a route?

“Nah,” said Quinlin. “Leonard’s just some guy who’s always up here.”

Quinlin said he’d been climbing for a year; Matthew and Carson were newly minted climbers. In fact, it was their first time climbing outdoors. All belong to the Triangle Rock Club, an indoor climbing gym in Morrisville. I saw a chance to establish some credibility.

“I belong there, too,” I casually mentioned.

“I thought you looked familiar,” said Carson. So much for credibility.

We exchanged questions. I asked what time they’d started climbing (9 a.m.), they asked if I’d come to climb. I explained that I wrote about the outdoors and had come up to do a presentation on backpacking that evening at the library in King.

“We backpack,” Carson said. “We’re into hammock camping. Wanna see my hammock?”

With that he pulled an Eno sleeping hammock out of his daypack and within two minutes had it slung between two trees.

“We quad stacked them once,” Carson said, and with that he showed me a photo on his iPhone of four hammocks strung above one another between two pines. “The top one’s about 15 feet off the ground.”

“What if the guy on top has to pee in the middle of the night?” I asked.

“You don’t want to be below him,” Quinlin answered.

Matthew got out his hammock. “I made mine,” he said. “I got $20 worth of ripstop nylon from Jo-Ann’s Fabrics and sewed it. I don’t really sew,” he added, “but for this you really don’t need to.” It was an ingenious invention of rope and fabric.

“What else do you guys do?” I asked.

“Slackline,” Carson smiled. The term rang a distant bell. Carson waited a respectful amount of time, realized I wasn’t going to answer the bell myself, and filled in the blank. Again, he pulled out the iPhone for visual reference and showed me a short video of himself tight-roping across inch-wide webbing strung between two trees.

“It was created by climbers looking for something to do in camp,” said Quinlin.

“How high off the ground are you?” I asked. The bright sun, screen glare and my not-so-bright eyes making it difficult to discern such details.

“Two feet? No, maybe five,” Carson said.

“It was a foot,” Quinlin corrected. “Six inches. It was on the ground.”

Despite a nearly two-generation age difference, I felt comfortable with these guys. We had some things in common — climbing (albeit on significantly different levels), a desire to be outside rather than in — and what we didn’t have in common — the energy and derring-do of youth — didn’t seem to matter. If I’d had my climbing gear with me, I’m sure they would have insisted I take a turn on the wall, and I would have felt perfectly safe entrusting my life to Quinlin’s belay. Nothing against the cell phone sisters — I have two at home just like them whom I adore — but these guys spoke my language. And they were speaking it at a much younger age than I had.

After an hour or so, after all three had at least one crack at Your Grandfather’s Belay, they were ready to move on.

“Should we do one more?” Quinlin asked. The consensus was yes. “We could do a 5.13” — the hardest climb at Pilot Mountain — “and call it a day.” I was reminded of innumerable, ill-advised black diamond last runs from my skiing days in college.

Matthew didn’t hesitate: “I don’t think that’s a good way to end the day.”