The following post originally appeared on June 5, 2019. We revisit it today because it’s always important to know where you are in the woods. And if you’ve lost track of where you are, it’s likewise important to be able to figure out where you are — and then how to get where you want to be. And if you’re the type who does better with hands-on instruction, check out our GetHiking! Finding Your Way in the Woods class, below.

I used to get lost. Now I just get turned around.

The difference?

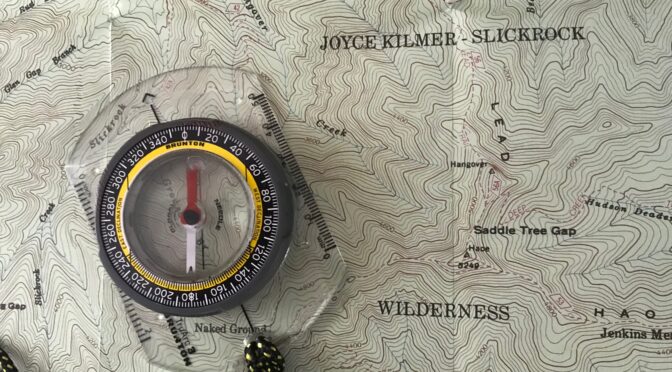

I no longer panic when I discover I’m not where I thought I was — or should be. And the reason I no longer panic is because I learned how to use a map and compass.

Let’s get something straight up front: I’m no Meriwether Lewis. I’m more a Ponce de Leon: eager to go in search of one thing, only to be distracted by something else. That makes it especially important to figure out where you are and the way to get to where you want to be.

When I decided to start leading people into the woods on hikes, I realized I needed to stay more focused. With a bunch of hikers in tow, I quickly discovered how embarrassing it was to think you’re in one place but are actually some place totally different. Just ask Columbus. So I started carrying a topo map, learned to use a compass, and I worked hard at figuring out how the map related to the terrain I was traveling. I learned that the wavy lines are called contours, which depict the elevation at a given point; that the closer together the contours are, the steeper the terrain; that as they emanate away from water, that means the terrain is rising. Those simple basics made figuring out where I was and where I was headed so much easier. And, for the most part, made it so much easier to figure out where I was when I discovered I wasn’t where I thought I was.

Where the heck am I?

One day a few years ago, I decided to take a lunch break and hike Eno River State Park. The Cox Mountain Trail is one of my favorites, and at 3.75 miles, I can get it done in a little over an hour. Hiked clockwise, it has a nice climb at the beginning, a generous descent on the backside of the mountain, a long return along the river. Just before reaching the loop portion of this lollipop, however, I noticed a narrow clearing — maybe 15 feet wide — that headed into the woods for maybe 75 yards, then vanished around a bend. The path was relatively clear … . What the heck, I thought.

Another reason to become familiar with a map and compass is so that when you do come across an opportunity like this — an old roadbed, a fisherman’s trail that’s not on your map — you’re more apt to check it out. Eno River State Park, like many state parks, wasn’t always a place of escape. In the Piedmont, most state parkland was actually farmland until the early 1930s, when the federal government began buying up overworked land and selling it to the state, cheap, for parks. Even though it’s been nearly 90 years in some cases, remnants of the cultivated past remain: a rock foundation, a stone boundary marker, ancient oaks signaling an old homestead, these roadbeds. Take one of these long-abandoned paths, pay attention, and you’ll be treated to a decaying blast from the past.

Ponce gets distracted

Which I did — and was. As often happens, I got caught up in searching for the past while neglecting the present. After a half hour or so, I found myself headed down a rocky tributary that I was sure would deposit me down at the Eno. Then I noticed I was following the tributary upstream.

“This won’t work,” I mumbled aloud.

Out came my map and compass.

First, I took in the surrounding terrain: an intermittent creek (appearing as a broken blue line on the map), a healthy slope to my left (tight contours), a generous floodplain to my right (no countours) and a steep draw straight ahead (tight, converging contours). Where I thought I was on the map didn’t look anything like this. I began searching the map for contours that matched my location, slowly scanning upstream until — bingo! And holy cow! I was nearly a half mile west of where I thought I was.

Lost — and found

But now I knew exactly where I was and how to navigate my way down to the river (which actually involved hiking atop a bluff rising 60 feet above a sharp bend in the river).

Was I worried? Only that I’d be back from lunch a few minutes late.

Learning to use a compass and make sense of a map isn’t genetic, it’s not an ingrained skill that either you can do or you can’t (like pole vaulting). Most of the folks who go through our GetOriented! Finding Your Way in the Woods class show up saying they have zero sense of direction. And usually after we spend a half hour or so going over how to read a map and how to use a compass, they still haven’t a clue. But as we head down the trail (and off), as we stop every so often and ask them to figure out on the map where we are, they almost always have an “Aha!” moment. The map suddenly makes sense, the compass no longer carries the mystique of a devining rod. Suddenly, their love of being outdoors isn’t overshadowed by their fear of getting lost in it.

Knowing how to use a map and compass doesn’t guarantee that you’ll always know right where you are in the world. But it’s a good bet it’ll keep you from getting lost. Just turned around.

* * *

Find Your Way with us

Love the trail but uncertain about your wayfinding skills? This three-hour session goes over basic map and compass skills, then hits the trail to offer key tips on how to follow and stay on the trail, how to find it again if you stray, and how to explore off trail. We’ll start with a 30-minute map-and-compass introduction, then use that map and compass — and some Daniel Boone skills — to find our way in the woods. We’ll also do some off-trail exploring, with the goal of purposefully venturing off the trail, then rejoining it again. Our goal is to make you confident hiking alone or taking a novice friend on the trail. Our next class:

Love the trail but uncertain about your wayfinding skills? This three-hour session goes over basic map and compass skills, then hits the trail to offer key tips on how to follow and stay on the trail, how to find it again if you stray, and how to explore off trail. We’ll start with a 30-minute map-and-compass introduction, then use that map and compass — and some Daniel Boone skills — to find our way in the woods. We’ll also do some off-trail exploring, with the goal of purposefully venturing off the trail, then rejoining it again. Our goal is to make you confident hiking alone or taking a novice friend on the trail. Our next class:

- GetOriented! Finding Your Way in the Woods: Wednesday, July 10, 6-9 p.m., Haw River State Park: Iron Ore Belt Access, Greensboro. Learn more and sign up here.