A few years back I was nearing the top of the Mount Mitchell Trail when I came across a group of youngsters intently examining the balsam firs that begin appearing above 5,500 feet. As they probed about, an older fellow explained what they were seeing. The gentleman had a professorial look; not surprising, I soon discovered, considering these were forestry students from N.C. State. I lurked in the shadows and got a free education on the challenges of life above 6,000 feet in a Southern Appalachian forest.

Sure be great if you didn’t have to go to school to get this kind of education, I thought.

Last night, I discovered, you don’t.

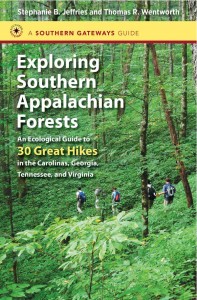

Before a packed house Tuesday evening at Quail Ridge Books & Music in Raleigh, Steph Jeffries and Thomas Wentworth discussed their just-released guide, “Exploring Southern Appalachian Forests: An Ecological Guide to 30 Great Hikes in the Carolinas, Georgia, Tennessee, and Virginia” (UNC Press). It’s a scientific look at the forest written for a lay audience.

Jeffries and Wentworth are uniquely qualified to write “Exploring Southern Appalachian Forests.” As N.C. State professors — she in the Department of Forestry, he in Plant and Microbial Biology — they’ve been exploring these woods for years. On one outing with students several years ago, Jeffries yelled to Wentworth: “We need to write a book about this.”

“Exploring Southern Appalachian Forests” is peppered with insights that can’t help but make a hike all the more enjoyable. A sampling:

Hope for the balsam fir. Most folks who’ve poked around much above 5,500 feet are aware that the balsam fir population has been taking a hit from the balsam wooly adelgid since the 1950s. Wentworth showed a shot of skeletal balsam fir tree trunks atop Clingman’s Dome to illustrate the point. Then he showed a shot of thriving balsam fir saplings in the same area. It’s too soon to tell if the balsam firs are coming back, he said, but it’s a hopeful sign.

Hope for the balsam fir. Most folks who’ve poked around much above 5,500 feet are aware that the balsam fir population has been taking a hit from the balsam wooly adelgid since the 1950s. Wentworth showed a shot of skeletal balsam fir tree trunks atop Clingman’s Dome to illustrate the point. Then he showed a shot of thriving balsam fir saplings in the same area. It’s too soon to tell if the balsam firs are coming back, he said, but it’s a hopeful sign.- Freeze your branches off. If you’ve ever hiked an exposed mountaintop and wondered why the trees only have branches on one side, there’s good reason. In winter, Jeffries said showing a slide of one-sided trees atop Grandfather Mountain, ice accumulates on the west side (from which most winter storms move in); the added weight snaps off the branches.

- Life’s a beech. Hiking the mile-long Summit Trail at Elk Knob State Park, I’ve often wondered why the ramrod-straight trees near the trailhead are so different from the gnarled ones up top. Turns out they’re both beech trees, but the ones near the top are exposed to howling winds and rugged weather, and end up being shaped by their environment.

- Fire good. Everyone fears a forest fire, right? Humans, perhaps, but not certain trees. The table mountain pine, for instance, relies on periodic fires to release its seeds from its resin-sealed cones. Human efforts at fire suppression over the years are threatening the pine’s ability to reproduce.

In addition to great insights, “Exploring Southern Appalachian Forests” provides the practical advice — including trailhead directions, GPS coordinates, trail length and difficulty — to plan and execute a hike on the 30 trails covering more than 100 miles in the book.

A great addition to your guidebook collection if you’ve ever stopped and puzzled over why a tree appears to be growing out of a rock. FYI, that tree would be a yellow birch, which can take root in the thinnest of soil — a bed of moss, for instance.

It’s in the book.

* * *

Like us on Facebook and get health, fitness and outdoors news throughout the day.