When I started writing about trails in the early’90s, my motto quickly became, “Getting lost, so you don’t have to.” It’s a philosophy I’ve stuck with as my scope has widened to encompass trying all kinds of things so you don’t have to.

A year ago, I had a backpacking class that included three vets, a rarity because most ex-military I encounter have zero interest in voluntarily spending another night in a tent. In our session on backpacking food, the topic of MREs — Meal, Ready-to-Eat — came up. Rather than the universal pan I was expecting from these three critics, the results were mixed. “Some aren’t bad,” they agreed. “But some are.” The next session, one of the vets pulled a brown cardboard box about the size of an iPad out of his pack and handed it to me. In dot-matrix type, it said “Egg Omelette with Vegetables and Cheese.”

The U.S. military version of MREs dates back to the Revolutionary War, when soldiers were dished enough peas, beef and rice to last a day. Field meals began appearing in cans by the Civil War, with a switch to salted and dried meals in WWI. The current MRE went into limited use in 1981 and became standard issue in 1986. Throughout, the emphasis has been on keeping the troops fueled, if not necessarily gustatorily happy.

I’d held onto my MRE, reluctant to tuck it into my pack in part because at at 8 ounces this single-serving breakfast weighs nearly 50 percent more than a Backpacker’s Pantry freeze-dried meal for two. (To be fair, the MRE includes a heating unit, eliminating the need to tote along a camp stove.) This past weekend, though, I decided an impromptu overnight to Falls Lake with a hike-in of less than a half mile allowed for the extra weight.

I spent a fair amount of time reading the packaging for my MRE, which came from AmeriQual Foods of Evansville, Ind. There was significant mention of performance (“Food gives you energy. The more energy you burn, the more fuel you need.”), not so much about taste.

I suppose after you’ve been living on these for a while, the six-step prep becomes rote. The first time, though, I figured it was crucial to get the prep right:

- Do not overfill the heating pouch with water

- Make sure the heater absorbs the minimal amount of water

- Make sure the heater is above the food pouch

- Make sure the heating bag is folded over the top

- Make sure that once the heating bag is inserted back into the pouch, the top of the pouch is elevated (on a “rock or something”).

- Then: wait at least 10 to 15 minutes for the magic to happen. (I waited 17, to be safe.)

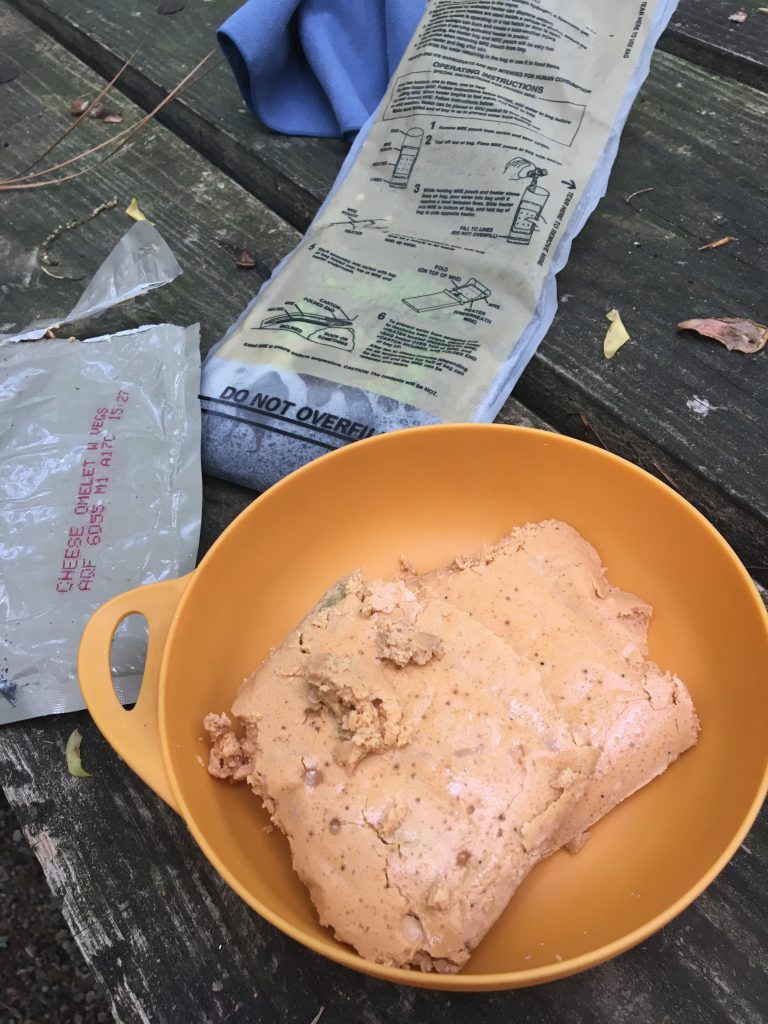

I then withdrew the pouch, which was not as warm as one might have hoped, and got out my knife to rip through the tough plastic pouch. I peered inside. My hopes were not high; I expected to see a whitish-yellow sludge with hints of green and red (the promised vegetables). What I saw was a thick paste (think caulk) the color of Carolina clay. The mass slipped out en masse into my bowl.

Could this possibly be among the “not bad” entrees my friends referred to? I took a bite: immediately the debate turned to “edible-or-not”? I ate a little more, because I was really hungry, jotted some notes, ate a little more.

No. Not edible. Definitely not edible.

True, the marketing-bereft packaging had not promised five-star dining. But its mere existence implied edibility, and on that note, they were incorrect.

Perhaps I had gone awry somewhere along the six-step preparation. I went back over the instructions; at the bottom of the box was the obligatory “CAUTION!” — “The contents will be HOT.” My contents were not.

Perhaps I hadn’t let the heater lie flat in its activating water for the requisite full minute. Plebe mistake. (This, my friends, is why you should always pack Pop Tarts.)

Trying MREs so you don’t have to.